|

EL AUTOR

Justino Llanque Chana nació en la villa de Suqa-Acora en el Perú. Realizó estudios en la Universidad Nacional del Cusco y Normal San Juan Bosco de Salcedo, ambos en Perú. Hizo estudios graduados en los EE.UU. en Antropología Lingüística y bibliotecología en la University of Florida y Florida State University, respectivamente. También, hizo estudios graduados en administración educativa en Andrews University en Berrien Springs, Michigan. Es miembro de la Academia Peruana de la Lengua Aymara (APLA), institución que promueve el desarrollo de la literatura Aymara y la concientización de la identidad Andina.

J. Llanque ha participado como especialista en la enseñanza de la lingüística Aymara desde enero de 1976. Actualmente, labora en la colección Latinoamericana de la University of Florida, forma parte del equipo de Proyecto Aymara que ofrece la enseñanza de la lengua en el Internet y continúa con las investigaciones lingüísticas y antropológicas para producir materiales en el área de lingüística histórica Aymara.

Más sobre el Proyecto Aymara

En la 56th Conferencia Anual del Centro de Estudios Latinoamericanos de la Universidad de Florida, EE.UU., 14-15 febrero de 2007, se hizo el anunció acerca de un programa de la lengua Aymara en el Internet, con el título de: “La Importancia de la Lengua Aymara en el Internet”.

También se ha presentado este mismo programa para Bolivia, en el mes de abril de 2008.

Como se anunció, los diálogos Aymaras están analizados elocuentemente con todas sus complejidades gramaticales. Sin duda, la página Web Aymara que adjuntamos tendrá un impacto alentador para las escuelas, universidades y población hablante del Aymara en general. Donde quiera que las computadoras estén al alcance de los usuarios, allí estará la página Aymara en el Internet.

Esperamos que el impacto sea a nivel nacional e internacional; porque los lingüistas, antropólogos y estudiosos de otras disciplinas podrán verificar, con todos sus detalles lingüísticos, lo que representa esta lengua. Estamos orgullosos que el Aymara sea presentado por primera vez en la Net de manera tal que explica exactamente la gramática estructural de la lengua en forma escrita y audible. La filosofía Aymara es muy diferente en muchos aspectos de las lenguas indoeuropeas, tales como en concepto, estructura, y fonología. La cultura Aymara tiene una manera diferente de concebir el tiempo, espacio, y las actividades humanas; además posee una manera única de indicar conocimiento personal o carencia del conocimiento personal, en cada oración.

Auguramos que este curso en el Internet será una gratificación y una experiencia enriquecedora para quienes desean estudiar esta lengua. Sin duda, esta Página Aymara tendrá un impacto imperecedero para las personas dedicadas a la enseñanza de las lenguas andinas. Evidentemente para los Aymara hablantes, será una experiencia motivadora. Por ende, les animará a practicar y utilizar orgullosamente su lengua en forma escrita y oral para mantenerla dinámica y vital para las futuras generaciones.

Además se incluye aquí la introducción de bienvenida en aymara, con la que inicia el programa:

Askipuniw purinipxtax aka aymar Internet sat wakichäwirux. Aka wakichatax uñacht’ayiw nayra wiñay inti jaqin arupa, sarnaqawipa. Yatiritakis jan yatiritakis taqpachan aymar ar yatiqañ muniritakiw wakicht’ata, sayt’ayata taqi amuyumpi. Aka lup’itax jichhakipuniw uñacht’ayasin akham qillqatamp, arsutamp kunjamatix jaqi arun amuyupas, illapas suk’antatäk ukanak. Aymar jaqin amtañapas, sarnaqäwipas mayjakipunirakiw yaqa markanakat sipans; amuy illapas, kunka ar illapas mayj mayjar arkst’atarakiw. Aymar jaqix mayjpunrak aka pachatuqits, jakañapats sarnaqawipats uñanuqt’asi, amuyt’asi. Arsuñatakis sumpunrak amuyt’asi, ukat, «Uñjasin, uñjt sañax, jan uñjasinx janiw uñjkt sañati» sas sapakut arsusin amtt’ayasi. Aka aymar ar lup’it wakichatax wakisiriphanall taqpach jumanakar uñancht’ayañatakis, yatxatt’ayañatakis. Taqi aymar ar arsur jaqinakax ch’amacht’apxañanill nayraqatar markas aptañataki qillqañamp, arsuñamp; ukhamarjamaw allchhinakasan allchhinakapas nayraqatarupuniw irptapxan jallallkiri, sap’alkiri wiñaypacha.

Aski amuyumpi,

Atentamente,

Justino Llanque Chana

Miembro del proyecto de la Lengua Aymara en el Internet

University of Florida

Gainesville, FL, EE.UU.

OTRAS ENTRADAS

EN

COLABORACIONES

COMUNÍQUESE CON EL AUTOR

COMENTARIOS COMENTARIOS

|

|

The objective of the present study is to analyze the linguistic-historical evidence of Jaqi-Aru as a language of the Wari culture. This study, at the same time, contributes to the delineation of the evolution of Andean culture, placing the Wari culture in the geographical and historical context of the Andean world.

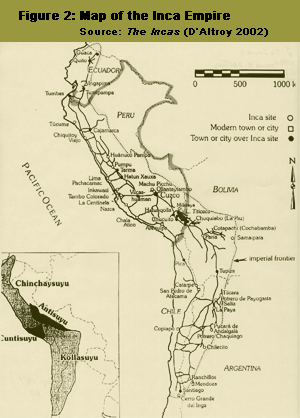

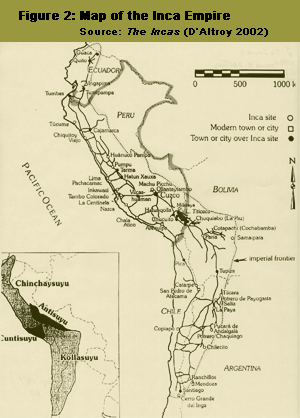

Before the arrival of the Spanish, in 1532, the Andean region was dominated linguistically by major languages such as Qhichua (Runa Simi), Aymara (Jaqi-aru) and Puquina; these languages were most extensively used as the form of communication, even before the advent of the Inca Empire (Torero 1974). In regard to Aymara, according to M.J. Hardman's linguistic research (2001), the Jaqi-aru family of languages that includes Aymara dominated the Andes from 400 to 800 AD. I include this information in this study in order to place in context the linguistic identity of the Wari culture, since the Aymara language has historical origins in that culture.

Chart 1

Andean Chronological Timeline and the Aymara (Jaqi-Aru) Language

Andean Chronology

| 900 – 200 BC (Early Horizon) |

Chavin |

| - 0 - |

|

| 600 – 1000 AD (Middle Horizon) |

Wari |

| 1200 – 1532 (Late Horizon) |

Inka |

| 1551 |

Juan de Betanzos: author of the Crónica Incas del Cusco (Cantar de Inca Yupanqui) |

| 1559 |

Polo de Ondegardo: uses for the first time the term Aymara Refers to the language Aymara |

| 1567 |

Garcí Diez de San Miguel: Visita a la Provincia de Chucuito |

| 1593 |

Visita de Acari: Cacique Don García Nanasca |

| 1612 |

Ludovico Bertonio: Vocabulario de la Lengua Aymara |

Native Chroniclers

| 1526-1615(?) |

Waman Puma: Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno, born in Lucanas, Ayacucho; speaker of three languages (Aymara, Qhichua y Castellano) |

| 1580/1585–1662(?) |

Pachacuti Yamqui Sallcamayhua: Historia de los Incas (Relación de Antigüedades Desde Reyno del Perú), born between Canas and Canchis; speaker of three languages (Aymara, Qhichua and Castellano) |

|

The archeologist Moseley (2006) indicates that the Wari Empire had an influence on the central Andes including primarily the Peruvian valleys of the western pacific between the years 500 and 1000 AD. With regard to evidence of the Wari culture in the central Andes in this chronological period, professor Lumbreras (2000) illustrates that the funeral bales and ceramics found in the Paracas archeological site are of Wari pan-Andean origin; the specific site where the archeological remains lie is in the archeological site of Wari-Kayan.

The Wari Empire's main cultural center in ancient times has been preserved as a historic site named Wari in the district of Quinua, in the province of Huamanga in the state of Ayacucho in the central Andes. The Wari culture had great influence in the central Andes. Archeologists such as the ethnohistorian Bauer (2004) note the cultural and archeological legacies that the Wari left us, such as roads, bridges, irrigation ditches, terraces, temples, and cities. (Fig. 1: Source: Lumbreras, L.G., Perú: Art from the Chavin to the Incas, 2006) The Wari Empire's main cultural center in ancient times has been preserved as a historic site named Wari in the district of Quinua, in the province of Huamanga in the state of Ayacucho in the central Andes. The Wari culture had great influence in the central Andes. Archeologists such as the ethnohistorian Bauer (2004) note the cultural and archeological legacies that the Wari left us, such as roads, bridges, irrigation ditches, terraces, temples, and cities. (Fig. 1: Source: Lumbreras, L.G., Perú: Art from the Chavin to the Incas, 2006)

Nevertheless, the ethno-historian Gary Urton (1990) has revealed the most linguistic details about the Wari culture’s presence in the Nasca valley of Peru, citing historical documents such as Visita de Acari (1593) a 16th century chronicle. In addition, Urton states that the National Archives (Lima, Peru) houses many documents with linguistic information including the titles to properties in the Nasca valley, as well as records of purchases and sales, and other details. These documents reveal evidence of the Wari culture, such as that the land had dual ownership in the traditional and Andean way. Urton deciphers from the documents that the main kurakas1 Don Garcia Nanasca y Don Francisco Ilimanga, were the heirs and traditional owners of valleys such as the Nasca valley in the 16th century (Urton 1990).

In these documents, the author also deciphers historical information about the Nasca valley, specifically social organization, geographical names or toponyms, and patronymic names (genealogy). In this aspect, the document indicates that the ayllus (communities) had Jaqi-aru toponyms and patronyms that today are still in use, such as Jaqui (Jaqi), from the ayllu Hakari (Jaqiri), from the ayllu Atiquipa, Atico, Collana, Chapara, Molloguaca, Caraville, Ocoña, Tirita, Acopana, Canta, Poromas, Collao, Samancaya, Humana, Achacone, etc. These names served in 16th century as geographical names and at the same time as genealogical names, as they are used today. In addition, the documents present a patronymic list, where every individual's name is recorded; here we find many Jaqi-aru names such as Martin Lucana Chana, Diego Pacari, Domingo Llallichana, Francisco Sullca, Juan Bilca, Marcos Umasi, Pablo Nanacsalla, Catalina Uricuzi, Francisco Jaymalla, among others (Urton 1990).

These documents and the historical information they contain are important for this study, demonstrating with authenticity that the language spoken in the Wari culture was one of the variations of the Jaqi-aru language family, of which Aymara is a major variation. For example, it is proposed that the current name of the Nasca valley was derived from the ancient patronymic and toponymic name for the ayllu (community) of Nanasca (a current Aymara word). In the Jaqi aru language family the word Nanaksa means “our land, our part, our side and that which belongs to our ayllu (community)”. Through the linguistic mechanism of metathesis2 (transposition of syllables in a word or between words), the “s(a)” and “k(a)” syllables were transposed over time from the Jaqi-aru word Nanaksa to Nanaska. The following chart analyzes the morphology of Nanaksa [na/nak/sa]:

| • |

the first syllable [na] is derived from the morpheme Naya which means “I” and “mine” (it is an allomorph of Naya); |

| • |

the syllable {-nak} is the morpheme [-nak(a)] which often drops the final vowel, and which is the plural marker; |

| • |

the demonstrative/possessive suffix [-sa], a suffix that means “ours.” |

Chart 2

Morphology of the word Nanasca |

| Nanaska/Nanaksa = na.nak.sa= our land, our own |

| Na(ya) = “I” or “I and mine” ; allomorph of Naya |

| -nak(a) = suffix that is a plural marker |

| -sa = demonstrative suffix, possessive |

Another word that is important for this study is the word Jaqi (Jaqui) which is an Aymara word in current use that means human. This word was found in the 16th century document "La Visita de Acari" (Urton1990); the widespread distribution of the word Jaqi in the central Andean valleys today indicates that the Jaqi-Aru languages were spoken in that area. In addition to being a common toponym today, Jaqi is a patronymic in many modern Andean communities. The toponym Jaqi is also currently found in the departamento of Arequipa which is in the province of Caraveli (Qarawilli) located in the district of Jaqui (Jaqi); and also in the departamento of Apurimac which is in the province of Cotabambas (Qutapampa) in the district of Haquira (Jaqi-ra).

Chart 3

Morphology of Jaqi |

| Jaqi = human |

| Jaquira [Jaqi.ra] = ayllu community (human) The suffix [-ra] denotes distribution in a series, and pluralizer |

| Jaquijahuana [Jaqi.qhawa.ña] = nominalized word that means a high lookout point from which to observe people approaching |

| Jaqiaru [Jaqi.aru] = compound word that denotes human language |

One can also find this toponym Jaqi in the province of Anta, Department of Cusco, for example in Jaquijahuana (Jaqi/qhawa/ña), where the famous civil war fought among the Spanish conquerors took place. Today, the Wari patronymic Jaqi (human) continues to be used as a last name, along with its variations Jaquiwa, Jaquini, and Jaquima. Another patronymic word is Aru (language) which is a current Aymara word that appears in last names with variations such Aruni, Arusquipa, Arucutipa, Aruntani, and Aruqa. Also found is the compound term Jaqaru (Jaqi-aru) which means human language and has variations including Jaqarusi, Jaquiru, and Jaqaruni. As mentioned above, these patronymics and toponyms are currently distributed throughout the central Andean valleys where the Wari culture developed. The examples mentioned here have been rewritten phonemically in some examples in this paper because they have undergone considerable transliteration since the 16th century.

The documents La Visita de Atico, La Visita de Arequipa and La Visita de Caraveli in 1549 (Galdos-Rodriguez 1976) among others, clearly demonstrate the social and linguistic reality of these regions during that time. In particular, La Visita de Acari 1593 (Urton 1990) verifies that the Pacific coast valleys were organized in ayllus (communities) that were interconnected and interdependent with ethnic groups from Lucanas and Aimaraes in the central Andes. In addition, these connections were at similar social, political, and economic levels with other central Andean populations. Further south, the Lupaqa kingdom was organized in a comparable manner. In the 16th century document, La Visita de Acari, the word Aimaraes has been altered by adding a redundant Spanish plural ending [es] to the basic word which already has a plural suffix {-ra}. The word has historical importance since it refers to geographic places and later the term (without the altered ending {es}) became the name of the Aymara language. There is sufficient evidence to indicate the meaning of the word Aymara: the historical information and dictionaries of the 16th century indicate the term jayma is defined as work executed for communal benefit, to profit the general community (ayllu). The meaning of the term remains the same today. Strong evidence suggests that the word jayma has evolved into Aymara, the name of the language, by adding the distributive and plural suffix {-ra}, as in the case of waylla/ra, qulla/ra, and uña/ra. The loss of the initial velar fricative {j} is common in today's Aymara language (Jayma becoming Ayma) due to Spanish influence3. It can be interpreted that the 16th century Wari settlers of the Aimaraes region were dedicated to communal work in communal lands to benefit the community, such as the construction of bridges, roads, irrigation ditches, housing, temples, etc., all of which were cultural characteristics of the Wari Empire.

Chart 4

Morfología de vocablo Aymara |

| Aymara(es) / Jayma.ra 4 |

Jayma = communal work that benefits the general population |

| -ra = suffix of distribution in a series, plural marker |

| -es = plural marker (Spanish influence) |

The chroniclers, witnesses who have closely followed the events of the conquest era, have left important documents. One such chronicler was Polo de Ondegardo (Llanque 1974) who in 1559 used the term Aymara for the first time to refer to the language spoken in the area. The chronicler Antonio Vasquez de Espinosa did the same in 1630, referring to Aymara as the second main language in the central Andes (Llanque 1974). But it was the eminent Jesuit Ludovico Bertonio who described the Aymara (Jaqi-aru) language in most plentiful detail. His work Vocabulario de la Lengua Aymara, published in 1612 in Juli (now located in Peru), is a historical document in which the author produces a list of names of the regions where the Aymara (Jaqi-aru) language was spoken between the periods before and after the Spanish conquest. In his dedication pages, Bertonio mentions that the Aymara nation consisted of several provinces such as Canas, Canchis, Pacajes, Carancas, Quillaguas, and Charkas. During the last centuries of the colonial era, in the Peruvian provinces of Canas and Canchis, the original Jaqi-aru languages were displaced by the Qhichua (Runa Simi) language, as cited in the above documents. In addition, the Bertonio document refers to those languages in general as Aru, meaning tongue or speech; for example, he refers to "Castilla Aru, Roma Aruni" [Bertonio 1612 (facsimile 1984)], meaning Castillian speech and Roman speech.

Documents describing visitas to Chucuito, Huanuco, Acari, Ica and Arequipa illuminate this study, interpreting the socio-economic, cultural and linguistic environments during the last Inca period and the first decades of the conquest. To explain these documents, we have the ethno-historian John V. Murra. The author, Murra, (1975) interprets the document La Visita Hecha a la Provincia de Chuchuito by Garci Diez de San Miguel in 1567 describing the Andean system of maximizing vertical control of ecological levels or zones, especially concerning the pastoral economy, weaving, agriculture and concerning the traditional ethnic authorities system of that time. In another document cited by John Murra, the chronicle El Padron de los Mil Indios Ricos de la Provincia de Chucuito, 1574, written by Frey Pedro Gutierrez Flores describes the accounts of properties and possessions of specific officials and communities. These documents demonstrate the harmonious interconnection between the societies of the Pacific coastal valleys, the jungle regions, and the Andean societies in the highlands; their interdependent harmony enabled them to make the most of the natural resources such as water, soil and other resources.

Therefore, in these documents, there is historical evidence of the socio-political traditions of the Wari culture that promoted political, social, environmental and economic Andean harmony. Even linguistically, these regions have coexisted in harmony from the middle horizon in archeological Andean chronology until the advent of the Inca society, as noted by the archeologist Mike Moseley (2001). The historical document La Visita de Chucuito, (1564) verified that there were Avmara-speaking (Jaqi-aru–speaking) kingdoms in the region; even today there are still Aymara-speaking people in the region. In fact, the first Aymara grammar and vocabulary were written in Juli by Bertonio in 1612, in the province of Chucuito which is now part of Peru). In addition, the native chroniclers also revealed the linguistic panorama from that time period. Among them are the chroniclers Guaman Poma de Ayala and Santa Cruz Pachacuti y Yamqui Sallcamayhua from the 16th and the early 17th centuries. Guaman Poma, included texts in Qhichua, Aymara, and Spanish in his work Nueva Cronica y Buen Gobierno (Urbano y Sanchez 1992).

These documents narrate in detail the activities of the Spanish colonists, and describe how they subjugated the Andean population. In order to write his document, the author Guaman Poma traveled for many years across the Andean villages as an interpreter and chronicler until he reached Potosi during his travels. Guaman Poma was a product of that historical time where languages intersected harmoniously and this is the reason that he was able to manage three languages: Qhichua, Aymara and Spanish (Ferrel 1996). Poma’s writings clearly indicated that today's provinces of Lucanas and other bordering places belonging to the current province of Ayacucho were Jaqi-aru speakers. The linguist Cerron-Palomino also verifies that people in the regions of Ayacucho, Cusco, Apurimac and neighboring territories were Aymara speakers at the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century (Cerron-Palomino, 1998).

Another Andean chronicler is Santa Cruz Pachacuti Yamqui Sallcamayhua, who professed to be a member of communities he called Anan and Urin (lower and upper) Guaygua, communities that he described as being located in the regions of “Canas and Canchis in Orcusuyos” which today are located in the state of Cusco. According to Bertonio, this territory once belonged to the region called Collasuyo, whose people spoke Aymara (Vocabulario de la Lengua Aymara published in 1612). In the 16th century, Pachacuti Yamqui Sallcamaygua spoke Aymara in addition to Qhichua and Spanish; at this time the Qhichua (Runa Simi) language started to spread and began to displace the Aymara (Jaqi-aru) language between the 16th and 17th centuries, approximately (Torero 1974). Pachacuti Yamqui drew minutely detailed diagrams, depicting the Incan Coricancha Temple, called the Temple of the Sun, with abundant images representing the Andean culture and religion, in his work Historia de los Incas. In these images he uses three languages: Aymara, Qhichua, and Spanish. Later someone mistakenly renamed this document Relacion de Antiguedades desde Reyno del Peru. (Urbano 1992).

By studying the 16th century Inca Cantar chant from Cusco, recorded by Juan de Betanzos (1551), additional evidence is found that the Aymara language (Jaqi-aru) was spoken in the Inca’s royal court in the central Andean region. This chant or song is also titled El Cantar de Inca Yupanqui and La Lengua Secreta de los Incas (The Secret Language of the Incas). Although this document has been interpreted by several other authors, the linguist Cerron-Palomino is the one who most effectively analyzed the linguistic details in a way that the other authors overlooked. He presented his case about the origin of the text of the Cantar document by verifying the phonological and morphological nature of the language used and placed the document in the historical and social context of the time. After analyzing the morphological, phonological and semantic structure of the Aymara, Qhichua and Puquina languages, the Cerron-Palomino concluded that the Cantar document indicates that the often-referenced “Inca secret language” was actually a variety of Aymara with a few Puquina traces.

Below, is a text that illustrates this connection from the analyzed chant (Cerron-Palomino 1998)

Chart 5:

Analysis of the Text of the Cantar of the Inca Yupanqui |

| A. Underlying Text |

B. Normalized Text |

Translation |

| 1. Inqa Yupanki, |

Ynga Yupangui, |

Inca Yupanqui, |

| 2. inti-na yuqa. |

indin yuca. |

son of the Sun. |

| 3. Suraya marka |

Sulay malca |

to the soras [placename] |

| 4. chimpu-ra-ya-i, |

chimbulayi, |

they put tassels on; |

| 5. suraya marka |

sulay malca |

to the soras |

| 6. aqšu-ra-ya-i. |

axculayi. |

they clothed them. |

| 7. Ha, way, way; |

¡Ha, waya, waya; |

¡Tanarara. |

| 8. ha, way, way. |

Ha, waya, waya! |

tanarara! |

Cerron-Palomino emphasizes that the Aymara language is a pan-Andean language and a predecessor of the Qhichua language that was still being spoken in the central Andes during the 16th and 17th centuries; in addition he adds that the above-mentioned text is a perfect model of Aymara (Jaqi-aru) language patterns as revealed in the linguistic structure. He even adds that the toponym Qosqo (Qusqu) is of Aymara origin. As previously mentioned in this article, the Avmara (Jaqi-aru) language continued being spoken in the central Andes during the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century and later was replaced by the Qhichua language. Finally, in the time of the next-to-the-last Inca, Wayna Capac, Qhichua came to be the administrative language of the Inca Empire; however evidence has been presented that the earlier Incas used the Aymara language as the official administration channel during the early periods of the Inca Empire.

At this point, authentic documents allow the conclusion that that the Aymara (Jaqi-aru) language has played a vital role in the history of the Andes. Even today, after more than five centuries of linguistic perseverance, other languages of the same Jaqi-aru linguistic family still survive, such as Kawki and Jaqaru; these languages are still spoken today in the province of Yauyos in the State of Lima. This evidence indicates that the Kawki and Jaqaru languages must have been interconnected with Aymara in Wari Empire times. These languages are important cultural legacies of Andean ancestors and living testaments of the cultural Andean identity.

In spite of external forces that impacted the cultural conscience of Andean people over a period of many centuries, Aymara is still the language of nearly three millions of inhabitants distributed across Chile, Bolivia and Peru. Campaigns for education, literacy, Castilian, catechization, and religion have functioned as instruments to repress Andean languages. For example, today Kawki and Jaqaru are endangered languages in the process of disappearing. The programs and education projects, as they have been practiced by official institutions such as schools, colleges and rural school centers, have been tools of linguistic and cultural destruction for these languages. These official institutions have generated cultural, linguistic and social alienation in all fields of Andean life.

Experts in this matter have poured out their opinions about this socio-cultural and linguistic problem. They say that true education would increase the social consciousness of the members of the community. Such a system would encourage the people to commit themselves to dignifying their cultural values, thus generating a mentality of self-confidence reminding people of their own cultural traditions and heritage, and imparting an integrated and coherent vision of their region, of their country and of the world (INIDE 1972).

The educational policies of the governments in Andean countries have been aimed at eradicating native language and culture, justifying such actions as being necessary for national unity. Without a doubt, centuries of colonization, exploitation, subjugation and discrimination have been detrimental for native language and culture. In the face of this reality, Andean people have opted for peaceful coexistence, accepting foreign and arbitrary impositions in order to survive culturally and linguistically to the present day. Given this historical situation since colonial times, the leaders of indigenous languages and cultures have protested loudly, demanding vindication for cultural, social, and economic injustices.

The revolts of Tupak Amaru and Tupak Katari from the 18th century and the uprisings of Aymara people in the 19th century in the Andean villages of Wanchu-Huancane, Willkas, Pumata, Quiñuani and Llallagua are latent manifestations in one or another period of the Jaqi-aru people reclaiming their liberation, rights, and justice in order to participate in their government and to reach their goal of redeeming their self-determination as a nation.

Current plans, community projects and bilingual education programs do not bear in mind the cultural, linguistic and social characteristics of the native culture of the Andean nations. The social and political movements that affect the Andean countries during the most recent times are manifestations of the public outcry to recover and vindicate cultural values which have been eradicated and destroyed.

The integrationalist governmental policies in the past have failed, resulting in alienation, domestication and indoctrination that have damaged and weakened native culture and languages, especially in the Andes. The discrimination against native cultures is due to lack of understanding on the part of the past and current administrations that has implemented exclusion of the native Andean people. In regard to that matter, Grondin (1970) reported that an Andean leader M. Ch’ila, had denounced the governments, saying that the result of Hispanicization and colonization had violated human rights. For this reason, he said, the official government programs were "inhumane, anti-historical and unpatriotic."

In spite of the resistance of the groups that teach racism and exclusion, there are Andean governments that are conscious of the socio-cultural and linguistic realities. These governments already have launched plans and educational programs to solve some of the most urgent problems. One of these is a program of bilingual and intercultural education to be supported in places where the native languages currently continue to be used. Undoubtedly, these programs will facilitate the promotion, preservation, and development of the languages for the majority of the people. In Peru, the Aymara-speaking populations have already emerged from the provincial and district municipalities. After the municipal elections of 2006, the Andean people declared themselves to be bilingual, making Aymara an official language along with Castilian (Spanish). Today, the Aymara language is used equally with Castilian, as the language of the official public administration. The provincial municipalities of Chucuito, Collao and the district municipality of Acora have also declared Aymara as the official language of their jurisdictions.

These institutions already have on their clerical staff experts in bilingual intercultural education. This way, they are already recovering ancestral cultural values, according to the cultural and linguistics reality in their territories. Official authorities from other jurisdictions are also breaking their traditional politics of racism and exclusion. In an effort to reclaim their cultural values, they are ratifying the initiatives of the native leaders and recognize the socio-cultural reality, granting participation to the popular bases that were always victims of social, economic and linguistic discrimination.

The Andean country of Bolivia has initiated plans and bilingual programs of profound changes for the Aymara, Qhichua, and Guarani people. The minister of education of Bolivia has announced in January 2007 that the government has initiated a program for dynamic development of the native languages as part of decolonization at a national level. The Aymara civil servant, Donato Gomez, currently active in Bolivia, adds, "We are fighting for legitimate rights, in this case our cultural identity" (Radio Patria-Nueva 2007). Currently the President of Bolivia has announced that there will be universities dedicated to teaching the Aymara, Qhichua, and Guarani languages.

In this social and historical context, it is hoped that this study will help to promote, preserve, and develop the rich Andean cultural heritage. Finally, this study responds to and supports the public outcry for an Aymara cultural and linguistic identity which has been denied for centuries due to subjugation and social discrimination.

Referencias

Bauer, Brian S., 2004: Ancient Cuzco : Heartland of the Inca, en Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long Series in Latin American and Latino Art and Culture. Austin:University of Texas Press.

Bertonio, Ludovico, 1984 (facsímile de original publicado en 1612): Vocabulario de la lengua aymara, en Serie Documentos Históricos, no. 1. Cochabamba, Bolivia: Centro de Estudios de la Realidad Económica y Social.

Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo, 1998: El Cantar de Inca Yupanqui y la Lengua Secreta de los Andes, Revista Andina: v. 16, no.2. Cusco, Perú: Centro de Estudios Rurales Andinos ‘Bartolomé de Las Casas.’

D’Altroy, Terence N., 2002: The Incas, Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers.

Ferrel, Marco A, 1996: Textos Aimaras en Guaman Poma, Revista Andina: vol. 14, no.2. Cusco, Perú: Centro de Estudios Rurales Andinos ‘Bartolomé de Las Casas.’

Galdos Rodrigues, Guillermo, 1976, Visita a Atico y Caraveli (1549), Revista del Archivo General de la Nación, v. 4/5. Instituto Nacional de Cultura: Lima, Perú.

Grondín, Marcelo, 1970: Nación Aymara, Oruro, Bolivia: INDICEP editores.

Hardman, M.J., 2001: Aymara, LINCOM Studies in Native American Linguistics: monograph no. 35. Munchen: LINCOM Europa.

INIDE (Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones para el Desarrollo Educativo), 1972: Revista del Maestro Peruano, Educación, Suplemento no. 4.

Llanque Chana, Justino, 1974: “Educación y Lengua Aymara,” tesis, Normal Superior de Varones, ‘San Juan Bosco’, Salcedo, Perú.

Lumbreras, Luis Guillermo, 2000: Las formas históricas del Perú, IFEA (Institut francais d'etudes andines), editores (Colección Alasitas). Lima, Peru.

Lumbreras, Luis Guillermo, 2006: Peru: Art from the Chavin to the Incas. Edited by Patrick Lemasson, Milan: Skira; London: Thames & Hudson (distributors).

Moseley, Michael E., 2001, Rev.: The Incas and their ancestors: the Archaeology of Peru. London and New York: Thames & Hudson.

Murra, John, 1975: Formaciones económicas y políticas. Instituto de Estudios Peruanos: Lima, Perú.

Silverman, Helaine, and Proulx, Donald, 2002: The Nasca, The Peoples of America series. Oxford: Blackwell.

Torero, Alfredo, 1974: El Qhichua y la Historia Social Andina, Lima: Universidad Ricardo Palma.

Urbano, Enrique y Sánchez, Ana, eds., 1992: Antigüedades del Perú, Historia No. 16. Madrid: Crónicas de América; Serie 70.

Urton, Gary, 1990, Chapter IV, “Andean Social Organization and the Maintenance of the Nazca Lines,” in The Lines of Nazca, Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society, no. 0065-9738, v. 183, Anthony Aveni, editor. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

1 A traditional leader who has authority in the community in the Andes

2 Metathesis (interchange of syllables) as in the case of ch’ullu versus lluch’u and tarwi versus tawri.

3 Current examples of the loss of the initial velar consonant [j] in Aymara exist today such as: ayu (salt) instead of Jayu; Amachi (bird) instead of Jamachi; and Ilave instead of Jilawi (place under jurisdiction of the older brother or jilaqata) in contrast to sullkawi (place under jurisdiction of the younger brother).

4 Ayma is also a toponym and a patronym; for example, note that the maternal last name of the President of Bolivia is Ayma (Evo Morales Ayma). In addition, there is a toponym Aymara located near the Mala river in the province of Cañete, Lima. |

The Wari Empire's main cultural center in ancient times has been preserved as a historic site named Wari in the district of Quinua, in the province of Huamanga in the state of Ayacucho in the central Andes. The Wari culture had great influence in the central Andes. Archeologists such as the ethnohistorian Bauer (2004) note the cultural and archeological legacies that the Wari left us, such as roads, bridges, irrigation ditches, terraces, temples, and cities. (Fig. 1: Source: Lumbreras, L.G., Perú: Art from the Chavin to the Incas, 2006)

The Wari Empire's main cultural center in ancient times has been preserved as a historic site named Wari in the district of Quinua, in the province of Huamanga in the state of Ayacucho in the central Andes. The Wari culture had great influence in the central Andes. Archeologists such as the ethnohistorian Bauer (2004) note the cultural and archeological legacies that the Wari left us, such as roads, bridges, irrigation ditches, terraces, temples, and cities. (Fig. 1: Source: Lumbreras, L.G., Perú: Art from the Chavin to the Incas, 2006)